ANCA-associated vasculitis

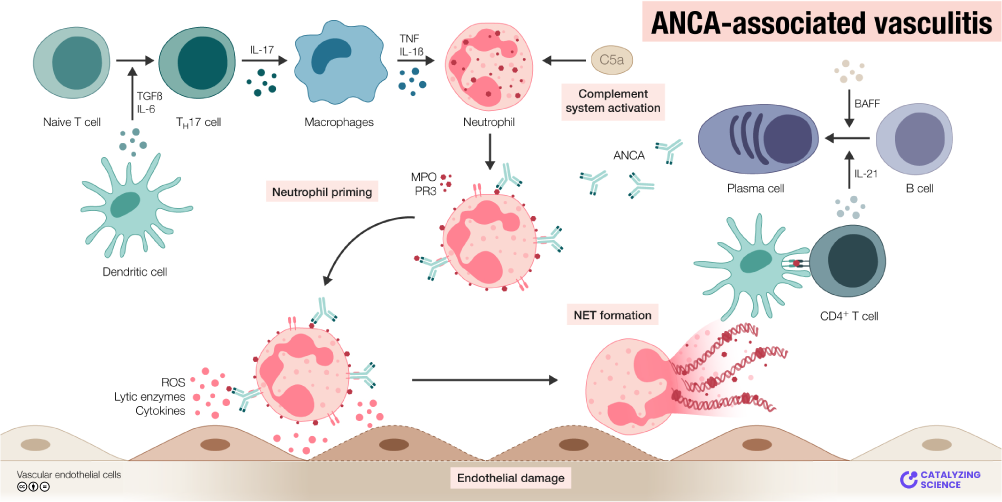

Group of small vessel vasculitides driven by ANCA autoantibodies, causing necrotizing inflammation with minimal immune complex deposition (*pauci-immune*). It includes Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (GPA, Wegener's), Microscopic Polyangiitis (MPA), and Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (EGPA, Churg–Strauss). ANCA (usually IgG against neutrophil enzymes PR3 or MPO) triggers neutrophils to attack vessel walls, leading to Type III hypersensitivity–like damage (immune-mediated small vessel injury).

- These vasculitides can cause life-threatening organ damage (renal failure, pulmonary hemorrhage) but are treatable with immunosuppression if recognized early. They often appear in exams as classic "pulmonary–renal" syndromes (hemoptysis + hematuria) with positive ANCA serology. Understanding ANCA vasculitis explains a key mechanism of autoimmune vasculopathy and guides prompt therapy to prevent irreversible organ loss.

- GPA (Wegener's) – Upper airway (ENT) + lung + kidney involvement (ELK). Presents with chronic sinusitis, otitis, or nasal ulcers (possible saddle-nose deformity from septal perforation), lung nodules or cavities (hemoptysis), and rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (hematuria). Often with systemic symptoms (fever, weight loss, arthralgias) and c-ANCA (PR3) positivity in ~90% of cases.

- MPA – Similar to GPA but no granulomas and typically no nasopharyngeal involvement (spares ENT). Causes necrotizing small vessel vasculitis with diffuse pulmonary capillaritis (alveolar hemorrhage causing hemoptysis) and pauci-immune crescentic GN (rapidly progressive renal failure). Associated with p-ANCA (MPO) in ~70–80%. Skin purpura and peripheral neuropathy (mononeuritis multiplex) are common.

- EGPA (Churg–Strauss) – Characterized by adult-onset asthma, allergic rhinitis/sinusitis, eosinophilia, and vasculitis with eosinophil-rich granulomas. Patients often have years of severe asthma/allergies, then develop pulmonary infiltrates (possible transient nodules/infiltrates but usually not cavitary), skin lesions (nodules or purpura), and neuropathy (foot or wrist drop from mononeuritis multiplex). About 30–50% are p-ANCA (MPO) positive, usually those with more vasculitic manifestations.

- Suspect AAV in any patient with an unexplained multisystem inflammatory disease, especially a pulmonary–renal syndrome (e.g. hemoptysis + rapidly progressive GN). Look for the triad of ENT, lung, and kidney involvement (suggesting GPA) or pulmonary hemorrhage + GN without ENT (suggesting MPA vs Goodpasture).

- Check ANCA serologies: perform indirect immunofluorescence for C-ANCA vs P-ANCA patterns and ELISA for PR3-ANCA vs MPO-ANCA specificity. A PR3 (c-ANCA) strongly points to GPA, while MPO (p-ANCA) points to MPA (or EGPA). Remember some patients (~10–20%) can be ANCA-negative; clinical judgment is key.

- Confirm with biopsy: Obtain tissue from an affected organ (e.g. kidney, lung, or nasal mucosa) for histopathology. Expect to see necrotizing vasculitis of small vessels with fibrinoid necrosis, often with granulomas in GPA/EGPA, and a pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis if kidneys are involved. Immunofluorescence will show little or no immune complex deposition, distinguishing AAV from immune-complex vasculitides (like lupus or IgA nephritis).

- Exclude mimics: Rule out infections (e.g. infective endocarditis can cause positive ANCA and similar presentations), other rheumatic diseases (e.g. lupus with vasculitis), or anti-GBM disease (Goodpasture syndrome, which causes lung+kidney findings but has linear anti-GBM deposits and no ANCA). Check anti-GBM antibody if pulmonary-renal syndrome, and consider ANA/dsDNA to evaluate lupus if appropriate.

- Once AAV is diagnosed (or strongly suspected), initiate therapy promptly (don't wait for biopsy results if life-threatening disease is present). Induction treatment with high-dose steroids + cyclophosphamide or rituximab can be life-saving. After remission, switch to maintenance therapy (azathioprine, methotrexate, or periodic rituximab) for 1–2 years and monitor closely for relapse. *Note:* ANCA titers may fluctuate and are not always predictive of relapses, so clinical monitoring (symptoms, labs, imaging) is paramount.

| Condition | Distinguishing Feature |

|---|---|

| goodpasture-syndrome | Goodpasture syndrome – anti-GBM disease causing similar lung hemorrhage + GN, but distinguished by linear IgG deposits on GBM, anti-GBM antibodies, and no upper respiratory involvement. |

| systemic-lupus-erythematosus | Lupus (SLE) – can cause small-vessel vasculitis & nephritis, but usually immune complex mediated (kidney biopsy shows "full house" IgG/IgA/IgM/C3 deposits) and has other lupus features (rash, arthritis, high ANA, etc.). |

| polyarteritis-nodosa | Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) – medium-vessel necrotizing vasculitis that typically spares the lungs and glomeruli (no alveolar hemorrhage, no GN), often associated with hepatitis B; usually ANCA–negative. |

| IgA vasculitis (Henoch–Schönlein purpura) | Leukocytoclastic small-vessel vasculitis due to IgA immune complex deposition (often in children). Presents with palpable purpura (typically on buttocks/legs), arthritis, abdominal pain, and IgA nephropathy – ANCA-negative. |

- Induction (severe disease): Start high-dose corticosteroids (e.g. IV methylprednisolone pulses, then high-dose prednisone taper) plus an immunosuppressant. Options include cyclophosphamide (classic choice) or rituximab – trials show rituximab is equally effective and often preferred, especially for relapses. For life-threatening presentations (critically ill with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage or rapidly progressive GN), consider adding plasmapheresis to remove pathogenic antibodies (particularly if concurrent anti-GBM antibodies).

- Induction (milder disease): If organ-threatening involvement is absent, a less toxic regimen can be used. For example, methotrexate (plus prednisone) can induce remission in non-severe AAV (conditional recommendation in guidelines). Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) is NOT a substitute for immunosuppressives in active disease, but it is given for Pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis during therapy.

- Maintenance: After remission (typically 3–6 months of induction), transition to lower-intensity therapy to maintain remission and prevent relapse. Common maintenance meds are azathioprine or methotrexate, or periodic low-dose rituximab infusions. Maintenance is generally continued for ~18–24 months. Monitor for relapse clinically; routine ANCA titer monitoring is controversial (rising titers may precede relapse but aren't perfectly reliable).

- If caused or triggered by a drug (e.g. propylthiouracil, hydralazine can induce ANCA vasculitis), remove the offending agent. Treat any concomitant infections before aggressive immunosuppression (active infections can mimic or trigger vasculitis).

- Mnemonic ELK for GPA: involves Ear, nose & throat, Lung, Kidney. If you see ENT + lung + kidney issues together, think GPA (Wegener's).

- PR3 = cANCA = GPA: The "3" in PR3 can remind you of the triad of GPA (ENT, lung, kidney) and that it's the c-ANCA disease. Conversely, MPO = pANCA = MPA/EGPA (think P for p-ANCA and Polyangiitis).

- Wegener's (GPA) classically can cause a saddle-nose deformity (nasal septum destruction). If you see an image of a collapsed nasal bridge in a vasculitis question, GPA is the answer.

- Remember that "pauci-immune" is literally "few immune complexes." So unlike lupus or IgA vasculitis, ANCA vasculitis has little to no antibody deposition in vessel walls – the damage is done by "rogue" neutrophils activated by ANCA.

- Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage – presents as acute shortness of breath, coughing blood, and new lung infiltrates. This is a medical emergency in ANCA vasculitis. It can rapidly progress to respiratory failure. Requires ICU-level care: high-dose steroids, cyclophosphamide or rituximab, and often plasmapheresis. Delay in treatment can be fatal.

- Rapidly progressive GN – manifested by a sharp rise in creatinine over days/weeks, oliguria, and RBC casts. Kidney biopsy typically shows crescents. In ANCA vasculitis this indicates severe disease; urgent immunosuppression is needed to prevent permanent end-stage renal disease. (Also rule out concomitant anti-GBM disease, which would double down on urgency.)

- Neurologic signs – e.g. a new foot drop (peroneal nerve palsy from mononeuritis multiplex) or strokes/seizures in the setting of vasculitis. These signal active widespread disease. Ensure prompt treatment; also assess cardiac involvement in EGPA if new neuropathy occurs, since myocarditis can be a hidden killer in EGPA.

- Patient with multi-organ inflammatory findings (especially lung + kidney, +/- ENT, skin, nerve) → suspect ANCA-associated vasculitis.

- Order initial work-up: ANCA panel (immunofluorescence and PR3/MPO ELISA) and basic labs (CBC, CMP, urinalysis for RBC casts, ESR/CRP). Perform chest imaging if respiratory symptoms (looking for nodules or infiltrates).

- If ANCA positive (or high clinical suspicion): refer to specialist and obtain a biopsy of involved tissue as soon as possible for confirmation. Do not delay therapy in a critically ill patient – you can treat empirically after obtaining biopsy samples.

- While awaiting biopsy results, exclude alternate diagnoses: e.g. get anti-GBM titer (to rule out Goodpasture), appropriate cultures (to rule out infection), ANA/dsDNA (for lupus), etc., based on presentation. This work-up helps ensure you're not misdiagnosing an infection or other disease as vasculitis.

- If diagnosis is confirmed (or highly likely): start induction therapy promptly – high-dose steroids plus cyclophosphamide or rituximab for severe disease (or consider methotrexate for mild cases). Provide adjuncts like TMP-SMX for PCP prophylaxis and calcium/vitamin D to mitigate steroid effects.

- Monitor closely during treatment: track renal function, pulmonary status (repeat imaging if needed), ANCA titers (trends may help, but treat the patient not just the titer). Once remission achieved, taper steroids and switch to maintenance therapy (azathioprine, MTX, or scheduled rituximab).

- Follow up regularly for signs of relapse (return of hematuria, cough, etc.). Educate patient on reporting hemoptysis or gross hematuria immediately. Relapses are treated with resumption of induction (often rituximab is favored for relapse). Ensure long-term surveillance for therapy complications (infections, cyclophosphamide-induced bladder toxicity or malignancy, etc.).

- A middle-aged patient with chronic sinusitis (nasal crusting, maybe a perforated septum), otitis media, hemoptysis from cavitary lung lesions, and rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RBC casts, rising creatinine). Lab shows c-ANCA (PR3) positivity → Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (Wegener's).

- A patient with a history of severe asthma and eosinophilia now develops fever, cough, new pulmonary infiltrates, tingling in extremities (mononeuritis multiplex causing foot drop), and purpuric rash. Labs: elevated IgE, p-ANCA positive. Biopsy shows eosinophilic granulomas in vessels → Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (Churg–Strauss syndrome).

- Rapid-onset hemoptysis and acute kidney failure (hematuria, RBC casts) in a patient without sinus/ENT symptoms. ANCA is positive (usually p-ANCA/MPO) → suggests Microscopic Polyangiitis (as opposed to Goodpasture, which would have anti-GBM antibodies and linear deposits).

A 52‑year‑old man presents with a 3-month history of sinus congestion, recurrent ear infections, and now cough and hemoptysis for one week. He notes unintentional weight loss and night sweats. On exam, he has a nasal septal ulcer and crackles in both lungs. Urinalysis shows numerous RBCs and red cell casts. Laboratory testing reveals a high titer c‑ANCA.

Graphical abstract illustrating the pathogenesis of ANCA-associated vasculitis. ANCA antibodies activate neutrophils (primed by cytokines like TNF-α) to release lytic enzymes and ROS, causing endothelial damage in small vessels.

image credit🔗 Knowledge Map

📚 References & Sources

- 1StatPearls: ANCA-Associated Vasculitis (Suresh & Zeng, 2023)

- 2UpToDate: Granulomatosis with polyangiitis and microscopic polyangiitis (Langford & Villiger, 2023)

- 3ACR/Vasculitis Foundation Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of ANCA-Associated Vasculitis (2021)

- 4Merck Manual Professional: Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss)

- 5New England Journal of Medicine: Plasma Exchange and Glucocorticoids in Severe ANCA-Associated Vasculitis (Walsh et al., 2020)