Rectal prolapse

Protrusion of rectal tissue through the anus. Can involve the full thickness of the rectum (complete prolapse) or only the mucosal layer (partial prolapse).

- Benign but potentially debilitating – causes discomfort, incontinence, and constipation if untreated. Frequently tested due to its surgical management and associations (e.g., cystic fibrosis in children).

- Most common in older women (peak incidence in 60s–70s) due to pelvic floor laxity. Rare in men over 40; when present in younger adults, often there is a predisposing condition (e.g., chronic straining, prior pelvic surgery, or neurological/psychiatric disorders such as autism or prolonged antipsychotic use).

- Patients describe a red mass protruding from the anus, especially during or after defecation. Early in disease it may retract on its own, but later often requires manual reduction. Over time, prolapse can occur with coughing, standing, or sneezing.

- Symptoms vary: ~50–75% have some fecal incontinence (mucus/stool leakage from stretched sphincters) and ~25–50% have chronic constipation or tenesmus (internal prolapse can cause outlet obstruction). Chronically prolapsed tissue can become thickened, ulcerated, and bleed (e.g., solitary rectal ulcer may form on the anterior rectal wall).

- Pediatrics: typically seen in infants and young children (usually <5 years) during straining or severe diarrhea. Often transient and self-resolves with conservative care as the child grows. Check for underlying causes: chronic constipation, malnutrition, parasites, or cystic fibrosis (up to 20% of CF toddlers develop rectal prolapse).

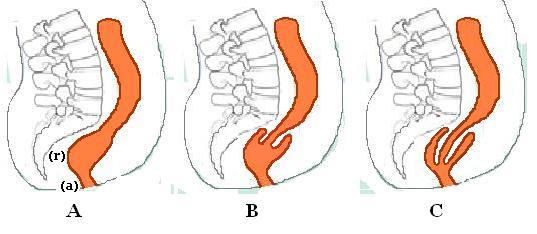

- Differentiate full-thickness vs mucosal prolapse: full-thickness prolapse has circumferential folds of rectal wall and a sulcus between the rectum and anus, whereas mucosal prolapse (often with hemorrhoids) shows smaller radial folds and no full circumference of tissue.

- Evaluate for contributors and co-morbidities. In adults, perform a colonoscopy to rule out a leading lesion (tumor, polyp) and because many patients are older with higher colon cancer risk. In women, examine for other pelvic organ prolapse (e.g., uterine prolapse, cystocele). In children, treat any reversible causes (e.g., constipation with laxatives, diarrhea) and screen for cystic fibrosis (sweat test) if unexplained.

- Document functional impact: assess incontinence (sphincter tone, frequency of accidents) and constipation severity. If obstructed defecation or refractory constipation, obtain defecography or colonic transit studies to identify internal intussusception or colonic inertia (which can influence surgical planning).

- Prolapse that becomes incarcerated (stuck) or discolored (possible strangulation) is an emergency – urgent reduction or surgery is needed to prevent ischemia/perforation. Applying granulated sugar to an edematous prolapse can osmotically reduce swelling and facilitate manual reduction in the interim.

| Condition | Distinguishing Feature |

|---|---|

| hemorrhoids | Prolapsed hemorrhoids (internal) are smaller, with bulging radial folds (often at 3,7,11 o'clock positions) and no concentric ring; can be very painful if thrombosed (whereas rectal prolapse is often painless unless strangulated). |

| rectocele | Posterior vaginal wall prolapse causing a bulge into the vagina and difficulty with bowel movements (in females); often coexists with rectal prolapse but is a distinct pelvic floor defect. |

- Start conservative management: high-fiber diet, adequate hydration, stool softeners or mild laxatives (to prevent straining), and pelvic floor exercises (Kegel/biofeedback). In children, treating constipation or diarrhea and improving nutrition usually suffices (most pediatric prolapse resolves without surgery).

- Surgical repair is indicated for persistent or full-thickness prolapse in adults (or any strangulated prolapse). Abdominal approach (e.g., laparoscopic rectopexy ± sigmoid resection) has the lowest recurrence rate and can also improve continence (preferred in young/healthy patients). Perineal approach (e.g., Altemeier perineal rectosigmoidectomy or Delorme mucosal resection) is less invasive (often used in older or high-risk patients) but has higher recurrence risk. Choice of procedure depends on patient's surgical risk and whether constipation or incontinence is present.

- For frail patients who cannot tolerate major surgery, a temporary Thiersch stitch (peri-anal silicone band) can be placed to prevent external prolapse, though this is used rarely and can have complications (e.g., erosion).

- In a child with rectal prolapse, always consider cystic fibrosis as an underlying cause (classic board association).

- Granulated sugar trick: sprinkling sugar on a prolapsed rectum helps shrink it (by drawing out fluid) so it can be more easily reduced.

- Strangulation: prolapsed rectum that is irreducible, dark, or extremely painful → risk of ischemia and perforation (requires emergent surgical evaluation).

- Chronic prolapse with new-onset bleeding or tenesmus: consider solitary rectal ulcer syndrome from repetitive trauma (mucosal ulceration that can mimic a neoplasm).

- Suspected prolapse → confirm by visualizing prolapsed tissue (have patient strain on a commode or squat if necessary) and distinguish full vs partial prolapse.

- Initiate conservative therapy: address predisposing factors (fiber for constipation, treat diarrhea, cough, etc.), avoid straining (stool softeners), and begin pelvic floor strengthening.

- If prolapse persists or is full-thickness in an adult → refer for surgery. Choose approach based on patient factors: fit patients often undergo abdominal rectopexy (laparoscopic if possible), whereas frail/elderly patients may undergo a perineal repair (e.g., Altemeier or Delorme procedure).

- Follow-up is important: monitor for recurrence or complications. In women, coordinate care for any coexistent uterine or vaginal prolapse; in children, ensure underlying conditions (like CF or Hirschsprung disease) are managed as the prolapse is treated.

- Elderly woman with a history of multiple pregnancies and chronic constipation who reports a rectal bulge that protrudes with bowel movements and must be pushed back manually.

- Toddler with failure to thrive and recurrent respiratory infections who presents with episodes of rectal prolapse during coughing or straining → suspect cystic fibrosis.

A 68‑year‑old woman with a history of multiple vaginal deliveries reports a "piece of tissue" prolapsing from her anus during bowel movements.

A 2‑year‑old boy with chronic cough and poor weight gain presents with episodes of rectal prolapse when crying or straining.

Full-thickness external rectal prolapse (procidentia) protruding from the anus; note the circumferential folds of rectal mucosa.

image credit

Grade IV hemorrhoids (mucosal prolapse of anal cushions) showing prolapsed mucosa with characteristic radial folds.

image credit

Diagram of an internal rectal prolapse (rectal intussusception). A = Normal anatomy, B = recto-rectal intussusception, C = recto-anal intussusception (the prolapsed rectum folds into itself but does not protrude externally).

image credit